“To get a good job, get a good education. Go to college.”

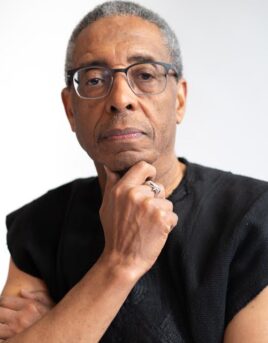

LOUIS HICKS

Class of 1969

“To get a good job, get a good education. Go to college.” This commercial repeatedly aired when I was watching my favorite television shows as an adolescent.

I was born in Austin, Texas, and grew up in the Austin Housing Authority’s Rosewood Courts (aka “Projects.”) Like many Black Austinites at that time, I navigated my way through a segregated community until I moved away to college. I am the third in a line of four children. Although I spent my elementary through high school years in a segregated school system and neighborhood, I felt nurtured. Relatives occupied at least six households along my street and the next intersecting street. That television message resonated with me because of my father’s similar message. He would continually ask my siblings and me to go to college. He had programmed me to believe that once I finished high school, college immediately followed. I can still hear his continual refrain: “Son, do one thing for me: Get an education. I don’t care if you go for just one year, go to college.”

I got a good education, and I got good jobs too.

- Programmed To Attend College

- Elementary, Junior High, and Senior Years

- My Journey to Attend College

- Attending College

- From A Good Education To Good Jobs

- Looking Back

Programmed To Attend College

As an adolescent in the 1960s, I loved watching television.

For many years Austin had one t.v. station and one channel. Lady Bird Johnson owned it. Her husband, Lydon Baines Johnson, was president of the United States from 1963-1969. The t.v.’s station management selected programs from the three major networks to fill out its daily schedule.

I spent many hours in the living room watching morning and evening programs. One commercial stands out — The Advertising Council’s one that targeted teenagers. I don’t remember the people in the commercial, but I remember the announcer’s voice-over message, “to get a good job, get a good education, go to college.” No doubt it featured a young white teen since we rarely saw national commercials that featured a Black one. Despite that, I thought the announcer was speaking directly to me. “The propaganda” worked. What’s weird? I don’t remember the commercial running during the school year began.

That message also resonated with me because my father continually asked my siblings and me to go to college. He programmed me to believe that once I finished high school, college immediately followed. I can still hear my father’s continual refrain:

“Son, do one thing for me, get an education. I don’t care if you go for just one year, go to college.”

My father had completed the eight-grade. He worked at the Terrace Motor Hotel as a porter (he referred to the position as a “Bell Hop”). My mother finished high school and later became a beautician. Many years later, I learned that not all Black schools in the United States consistently provided education through the twelfth grade.

I am the third child in our family. Two other siblings heeded my father’s request and attended college. Of the three of us, I was the only one to finish a four-year university with degrees (two undergraduate degrees- a B.A. in psychology, a B.F.A. in studio art, and a master’s degree– African art history).

Elementary, Junior High, and Senior Years

Texas schools divided its public schools into three levels – elementary school (K-6th), junior high school (7th-9th), and senior high school (10th–12th).

Racial Segregation: Before entering high school, I spent my elementary through junior high school years in an all-Black environment. The elementary, junior, and senior high schools were near my house. I could easily walk to school in less than 30 minutes. The majority of my public-school experience was within a segregated student body. African American students attended schools within their neighborhood.

At that time, my community, East Austin, was racially segregated. White teachers didn’t teach me until my sophomore year (1966) in high school. Although Black students and Latino American students may have lived in the same neighborhood, they attended segregated schools. The student body was exclusively white, Latin, or Black. A handful of white teachers taught in segregated schools.

Half-Time Shows & Marching Bands: In Texas, as long as I can remember, football has been “KING” of sports, and it still is. In my community, the neighborhood high school Friday night football games were a significant social activity for the community as a whole.

Playing sports in Texas was a “rite of passage,” especially playing football. I played football in the street and the backyard with my neighbors. I was a reasonably fast runner and had considered running track. Students had to choose whether to play sports or play in the band. I chose “band.”

Why?

The half-time marching band show was as much of an attraction as the actual football game in junior high. The marching band’s half-time show pageantry impressed me. The band didn’t just march onto the football field, play, and leave. While marching and playing their instruments, they performed choreographed routines with majorettes dancing to the music.

No doubt, this “show” inspired me to join the band once I reached junior high.

Elementary School: The clarinet was my first musical instrument in the 6th grade. I began studying it, not because I chose it. My older sister had abandoned it.

I inherited her clarinet when she reached eight-grade and started playing a school-owned bass clarinet. Since my sister’s clarinet was lying around the house, my parents decided to give it to me rather than purchase a new or different instrument. Undoubtedly, it was “economics.” Hand down an instrument rather than buy a new one. My father told me that the old clarinet was mine and I would learn to play it in school, and I did.

Junior High School: In my junior year in high school, the marching band director noticed that the band had too many woodwind instruments and not enough brass ones. He asked if anyone would be interested in switching instruments. I eagerly volunteered to learn to play the French horn. I only remember four other students from the flute and clarinet sections raising their hands and joining me to learn a new instrument. During the remainder of the school year, the band performed music for school assemblies and an annual two-hour musical concert in the spring of each year.

High School: I enjoyed my years in L.C. Anderson High School. I didn’t think that anything could get better than high school. While I consider myself something of an introvert, I’ve always found it easy to make friends. I knew the names or recognized 85% of the approximately 500 students in my school.

My sophomore year in high school doesn’t hold any particular memories except for one. I loaned my yearbook to my best friend, and he never returned it. My school produced yearbooks every other year. Fortunately for me, there would be a yearbook for my sophomore and senior years.

Since I had lost my sophomore yearbook, I decided to join as many school clubs as possible to document my time in high school. I joined the drama club, the prom planning committee, and a few other groups so that my name would appear more than once in the Index.

During the homecoming football season that year, I was one of four candidates competing for the title of “Mr. Esquire.” We each had to give a three-minute speech in front of a student body assembly to explain why our fellow students should choose us.

Although I had rehearsed my speech and thought I had it under control, I “shook like a leaf” on stage. After losing the competition to Nelson Robinson, I soon realized my naivety. We weren’t competing on “scholarship,” the merits of ones’ character, or the points of speech delivery. Instead, the criterion was “popularity.”

Despite losing that competition, my classmates chose me as a class favorite for “Most Modest” and “Most Courteous.” I still have mixed feelings about these titles.

My Journey to Attend College

College Mis-Counseling: After a meeting in my junior year with the high school’s guidance counselor, the counselor almost derailed my plans to attend college. He reviewed my grades and went over the necessary steps to apply to the colleges I wanted to attend. He then told me that “I was not college material.”

His words crushed me!

Firmly cemented in my mind were the television’s message and my father’s expectations. I didn’t know what to do.

Later that evening, when I repeated the counselor’s comment. My father simply replied, “forget what he said; you’re going to college.” My father had mapped plans for my future. He wasn’t going to allow a college high school counselor to foil them. For my father, I didn’t have the option of not attending college.

Vietnam War. I’m not sure whether it was in the summer between high school and college when my father suggested that I join the armed services as an alternative to going to college. Like most parents, in an attempt to secure an offspring’s future, my dad sometimes suggested that if I didn’t go to college, I should consider joining the Armed Forces.

Why did he see the Army as an alternative to college?

After having served in the Army, one would receive long-term benefits — a stipend to enroll in college with funds from the G.I. Bill; free Veterans health care at a Veterans hospital; and permanent old-age residential care in a Veterans hospital.

However, this was the peak of the Vietnam War. I was scared at the prospect of joining the military.

Evenings during the national news broadcast, the anchors reported the number of war casualties. I couldn’t imagine I could kill someone. I also doubted whether I “had what it would take” to make it through basic training.

The media covered Cassius Clay’s (later Muhammad Ali) conscientious objection to the war in Vietnam. I sympathized with Ali and briefly entertained thoughts of running off to Canada to escape being drafted into the Vietnam War.

I didn’t know anyone in Canada, nor did I think about how I would survive should I escape there. However, fleeing to Canada was always in the back of my mind if my draft number was a low one.

When young men reached their 18th birthday, they had to register for the U.S. Selective Service draft. A lottery system assigned numbers to your birthday. If your number was a low one, your chances of being drafted and sent to Vietnam were extremely high.

But there was an escape.

Student Deferment: Student deferments allowed young men to avoid the draft. They could enroll in a college or university. I graduated from high school in the Spring of 1969 at the age of 17. My birthday is on the last day of August. When I turned 18 years old, I registered for the draft. I “hit the jackpot.” My number – 255 – was low enough that there was a high probability of being drafted.

Attending College

In the fall of 1969, I enrolled in the University of Texas at Austin (U.T.). Since U.T. was a state school, the tuition was relatively inexpensive. I believe my father paid about $500 per semester for my course load.

When the time came for me to declare an undergraduate major at U.T., I decided to study psychology and pursue a liberal arts degree. Reading horoscopes had inspired me because of the way they predicted human behavior. I thought studying psychology would give me more in-depth insights. And it did.

I lived at home and commuted to school. I had a short 20-minute drive from my house to the student parking lot.

I was an average student in high school with a “B” average, but I didn’t have very good study habits. I graduated in the upper percentile of my high school class of 150 students. When I arrived on the university campus, I experienced “cultural shock.” I had to adjust to a student body of 35,000 students, where the average lecture class enrollment was 500 students for a freshman course.

I struggled to figure out the course material throughout my first year and find a suitable place to study. I tried the library, the student union, and my bed in a room that I shared with my brother. No matter what, within thirty minutes or less of studying, I would fall asleep after only getting past three or four pages of reading.

A year later, I would find out “eye strain” caused my “sleep issue.” I needed glasses.

My grades were terrible at the end of the first year. When I returned for my second year, I was on academic probation. I had a year to improve my grades. If expelled, I feared that I would be drafted and sent to Vietnam.

Luckily for me, three or four high school friends also attended U.T. They told me about an African American woman staffer in the student services division. The Black students affectionately referred to as “Mama Duren.” She helped me enroll in a speed-reading class, a study habits class and guided other students and me through the university bureaucracy’s maze. By the end of my sophomore year, I pulled my “D” grade point average up to 3.0.

From A Good Education To Good Jobs

Upon graduation from U.T., I had to figure out my next steps quickly. I held a liberal arts degree in psychology. I hadn’t received any career guidance. Consequently, I didn’t know that I needed a graduate education to be a certified psychologist.

Substitute Teaching: I now needed to find a job. I was fortunate. The Austin Independent School District hired me as a substitute teacher. Each assignment lasted for two or three days. It seemed like easy work. I requested to teach “special education classes.” Toward the end of the school year, I worked for almost a month to finish out the spring semester due to a teacher’s health condition.

Permanent Teaching: The principal offered me a job teaching, but a permanent position required a teaching certificate. She liked my work and suggested that I go back to school to get the required teacher’s certification. I thought that since I had more than 125 hours of coursework for the psychology degree, I could finish the work on a teacher’s certificate in a year or two.

I enrolled in U.T.’s School of Education program. I spent one day in class and realized I was bored by the material. I knew that I wasn’t a disciplinarian and would have a hard time controlling the students.

An Art Major: Before graduating with my degree in psychology, I had enrolled (pass/fail) in a life drawing class in U.T.’s art school. With just a few minutes in a graduate education class, I decided to shift from my major from “education” to “art.” The next day, I enrolled in the art school and thought that I could quickly get a second degree in art. It took me four years to complete the degree. In my final year, I concentrated on commercial adverting. I dreamed of going off to New York and working in an advertising agency.

Museums: Once again, I finished school without any clear job prospects. While completing my art degree, I worked in a neighborhood library. My supervisor told me that a museum was going to open under the library department. The museum’s home would be the building that was previously my neighborhood branch library. He suggested that I apply for the museum’s curator position.

I ended up working at the George Washington Carver Library for eight years. On-the-job, I began to clearly see the harmful effects of Black people’s not being fully represented in American history. I developed a thirst for knowledge about the history of Blacks in Austin, Texas. The quenching of my thirst inspired the exhibitions I created during my tenure as director/curator.

While I enjoyed my job, I wanted to advance professionally. I set my sights on the East Coast. I frequently read the museum association’s newsletters and scanned the position announcements to see what qualifications I needed to advance. I was now consciously directing my career.

Get this! I started with “qualifications” and worked back to courses.

Howard University (H.U.) offered me a scholarship to earn a Master’s degree in African Art History. I enrolled in 1988, and I finished my degree in 1992. A decade or more after undergraduate school, I discovered that tuition in a private school like H.U. was much more expensive than a state school’s cost. U.T.’s tuition was $500 per semester. H.U.’s was $12,000. Fortunately, I had received a scholarship waiver, and I didn’t pay tuition while studying at Howard.

I was fortunate to have worked for eight years as a City of Austin employee before moving to D.C. While working in a museum, I received financial counseling through the city government and a private financial service. I accumulated a modest financial portfolio through American Express Financial Services. I was able to tap into those resources for extra cash to supplement my income while attending Howard. Also, I participated in a “work/study” program during my four years at H.U.

I worked for six years at the Anacostia Community Smithsonian Museum (ACSM) as a “Special Assistant to the Director.” I described my role at ACSM as running a museum (a community one) within the museum (The Smithsonian national museum). At ACSM, I wore many hats (public relations, supervisor, gift shop coordinator, special events coordinator, traveling exhibits manager, and community gallery curator).

While working at ACSM, I began to look for a higher-paying job. I applied for a museum director’s position at the City of Alexandria, Virginia’s Black History Museum. They hired me, and I remained there for 15 years until I retired in 2013.

Humanities: My retirement lasted two years. I was anxious. I wanted to fill my time. I looked for jobs that matched my skills. In 2015, HumanitiesDC hired me as a “Grants Officer.” I served in that position for four years and retired once again.

Now for the second time, I was looking for something to do. I was planning to offer “event planning services” as a new business, but then COVID-19 hit. My business is on hold.

Looking Back

I am so thankful that my father inspired and paid for me to go to college.

I often think about where I would be today had I remained in Austin. As a result of moving to D.C., I have traveled internationally throughout Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central and South America. I have developed a stronger identity as an African American due to my work in African American museums. Throughout my professional career, I have worked with internationally recognized celebrities to fulfill my job responsibilities.

Why was my father so keen on my siblings and me getting a college education?

He told me that he had to drop out of school when he was a teenager to work in the cotton fields to support his mother and siblings. He wanted his children to get the educational opportunities he didn’t have.

In August 2020, my father celebrated his 94th birthday. As often as I can, I thank him for motivating me to go to college. I am one of his dreams that became true.

If you are enjoying The 1960’s Project, please consider making a contribution to the…