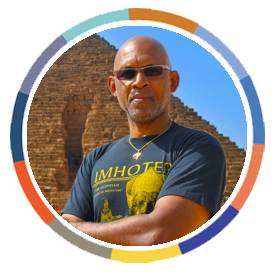

DR. ANTHONY BROWDER

To my daughter Atlantis and all the young people who view me as a role model: I was born in 1951. As I approach my 70th year, I trust my reflections of the 1960s will help you understand the legacy you are inheriting and why you must use, preserve, enhance, and transmit it to the generations that will follow you. What continues to be important to me is educating and empowering my people. With each generation, we can educate and empower each other.

- Malcolm and Muhammad Al

- Martin Luther King, Jr.

- My Integrated High School Years (1965-1969)

- Motown and the Rise of Black Consciousness

- My Freshman Year in College

- Looking Back

- Next Steps

Coming of Age in the United States of “Contradictions”

Growing up in Chicago was like living in Dickens’ “Tale of Two Cities,” where people on one side of town experienced the “best of times” and people on another side of town experienced “the worst of times.” These political and social forces in Chicago were created decades earlier as increasing numbers of Black families migrated North seeking better opportunities. My grandparents migrated to Chicago from Alabama in the late 1930s. Back then, Chicago was the most racially segregated city in the United States. It still is today.

I was born in an all-Black community on Chicago’s West Side when restricted covenants were the law, and violating them was punishable by physical abuse or death. In hindsight, some of these restrictions were a blessing because I grew up with black dentists, doctors, bankers, and dermatologists and had many examples of Black professionals who had overcome adversity to inspire me.

The news in white-owned papers, TV, and radio stations frequently talked about the crime and violence in our community, but we had Jet, Ebony, and the Chicago Defender to give us another perspective and tell us about the positive things Black folk were doing in the city and around the country.

I came of age in the 60s, and my world was shaped by the Four M’s: Malcolm, Martin, Muhammad Ali, and Motown. The Four M’s defined the 60s and made it one of the most significant decades of the 20th century.

Malcolm and Muhammad Ali

I was 13 years old when Malcolm was assassinated in 1965 and did not grow to understand the full impact of his life and death until I read his autobiography as a college freshman in 1969. All I knew was that the people who mourned Malcolm’s death loved Muhammad Ali because of the way he “stick it to the man,” inside and outside of the boxing ring. Muhammad Ali’s refusal to join the army and fight in the Viet Nam War because “No Viet Cong ever called me Nigger” was a source of inspiration for young men such as myself who were draft age.

A close family friend operated one of the businesses the Nation of Islam (NOI) ran near their headquarters on Chicago’s South Side. I recall him taking me to see their grocery store and telling me of the farmland the Nation owned in the South from which they grew, processed, and shipped all the items in their stores in Chicago. It was called “Your Grocery Store,” and all the products carried the “Your” brand. If they didn’t make it, they didn’t sell it—what a beautiful display of the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles of Kwanzaa. The Nation of Islam (NOI) was practicing these principles a decade before their official articulations in 1966.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

I was ten when I became aware of the words “segregation,” “prejudice,” and “discrimination.” I found it difficult to grasp these concepts and understand the social norms that were created to keep my parents, grandparents, relatives, and friends “in their place.” I remember when Dr. King attempted to integrate the all-white neighborhood of Marquette Park on the near South Side. Dr. King was hit in the head with a brick on August 5, 1966, as he approached his rented apartment. Dr. King later commented on the evening news that he had never faced such a vicious mob in all his years of demonstrating in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. Mayor Daley told Dr. King that he would be unable to protect him in Marquette Park and “encouraged” him to move his protest to a housing project on the Black side of town . . . which Dr. King promptly did.

I was 16 when Dr. King was assassinated, and I watched smoke fill the skies from the fires set in the business district in my neighborhood. In 1968 there were few places my parents, grandparents, and other Blacks could shop downtown, so we relied on the white-owned businesses in our neighborhood for goods and services that were often sold at inflated prices. Dozens of businesses were burned to the ground between April 4-6, and none were ever rebuilt.

My Integrated High School Years (1965-1969)

My high school years were the first time in my life that I was a minority in the classroom. I had attended the same elementary school my mother and her siblings attended. It was an all-Black school, and half the teachers were white. In this space, I grew to love school and was nurtured by teachers who encouraged my love for learning. After graduating from Middle School, my mother felt that the all-Black high school that she and her siblings had attended had fallen on hard times, so arrangements were made for me to integrate Austin High School on the far West Side. I experienced two “Race Riots” during my Freshman year at Austin. My mother decided to move to Oak Park, IL, so I could attend a better school and continue my education without fear of my being attacked or killed by whites.

We were the second Black family to move to Oak Park IL 1966. Oak Park is a small suburb west of Chicago, and during the three years we lived there, I was one of only two Black students attending Oak Park River Forest High School. There were no Black teachers, office workers, or custodians at my new school, but I grew accustomed to being the only black body in a sea of whiteness. I got along well in Oak Park and made friends with guys who had never known any Blacks and were continually surprised that I fit none of the stereotypes they had grown up believing about Black people. The one thing that made life in Oak Park bearable was that I frequently spent weekends at my grandparents’ home on the West Side and maintained close relations with all my childhood friends.

Motown and the Rise of Black Consciousness

The lives of most high school students (then and now) revolve around music and parties. I was blessed to grow up during Motown’s heyday when the Temptations, Marvin and Tammy, Mary Wells, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, the Supremes, Four Tops, and Little Stevie Wonder were the soundtrack of our young lives. Their music made life worth living, and their songs reflected the ever-changing times in which we lived. This was the time of Black Power, Black Consciousness, Afros, and dashikis, and the music shifted from love songs to songs of protest and Black empowerment as the Souls of Black folk cried out and sang songs of “Freedom.”

In Chicago, Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions sang “We’re a Winner” and “Keep on Pushin,” while the Chi Lites sang, “Power to the People.” James Brown took us to higher heights with a new national anthem that spoke of a new day. “Say it Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud” was the Declaration of Independence of a people who now sought freedom “by any means necessary.”

In August 1968, racial tensions were at an all-time high. Dr. King had been murdered four months earlier, the VietNam War was still raging, and Chicago was hosting the Democratic National Convention. I recall driving on the Eisenhower Expressway with my friends from the West Side when we spotted a car with Alabama tags, dixie flags, and a George Wallace for President bumper sticker. James Brown’s national anthem was playing on the radio as we pulled up alongside the Alabama car. We rolled down our windows, turned up the radio, pumped our fists in the air, and shouted “Black Power” until the car full of Alabama Dixiecrats exited the highway to escape our menacing gazes.

My Freshman Year in College

I graduated from OPRF High School in June 1969 and attended the University of Illinois Circle Campus in the fall where I majored in Architecture and became active in Black activities on Campus. Our school was on the near West Side, not far from the Black Panther Headquarters, and the Panthers were a frequent presence on campus. I remember a conversation a group of us had with a classmate (Brenda Harris) who was in the apartment the night Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were murdered by Chicago police and federal agents on December 4, 1969.

I recall Brenda’s version of the shooting differed greatly from the “official” version of events repeated by politicians and police officials in the local news outlets. Hearing the first-person account of Fred Hampton’s and Mark Clark’s murder made me keenly aware of the reality I came to know growing up in Chicago. It is a reality now referred to as “fake news.”

There is no doubt that the activities and events in the 60s shaped the history of America and the world. The spirit of the 60s is in the Black Lives Movement’s DNA and the current protests against police brutality and Black voter suppression. That spirit reminds me that the more things change, the more they will remain the same until they are met with an equally opposing force, which brings about fundamental changes for future generations.

Looking Back

As I look back on my life, I can see clearly how the events of the 60s shaped me and taught me important lessons I have used throughout my life.

Pursue self-employment.

To avoid being treated unfairly in the workforce, I started my own business in 1979. Operating my own design studio allowed me the freedom to make as much money as I wanted and to use my time and resources to study Black History and learn from the people who inspired me.

Create forums to share your knowledge.

After returning from my first trip to Egypt in 1981, I launched my first social enterprise (IKG) in 1982. IKG was a vehicle for me to share my expanding knowledge of African and African American history and culture with my new community in Washington, DC. Over the past three decades, through my work at IKG, I have authored and co-authored 14 books that are currently used in schools throughout the U.S. and around the world.

In 1994 the Black teachers at Oak Park River Forest High School invited me to speak to the student body about my experiences there in the 1960s. OPRF is now 40 percent African American and Latino. The teachers had been using my books to teach history. That evening I was entered into the OPRF Hall of Fame, where my picture now hangs on the wall with Ernest Hemmingway and other distinguished alumni.

In 2008, I established my second social enterprise, the ASA Restoration Project, and began funding excavations in Egypt. We are the first people of African ancestry to fund and participate in Egyptian excavations and have unearthed eight 2700-year-old tombs. The project is named in honor of my friend Dr. Asa Hilliard and is dedicated to restoring Egypt’s 25th Dynasty’s historical legacy.

Next Steps

Atlantis, as I approach my 8th decade of life and my 4th decade as a social entrepreneur, I’m turning over my businesses’ day-to-day operation to you and four other millennials who I’ve been grooming for more than 15 years.

I trust my reflections of the 1960s will help you and our colleagues understand the legacy you are inheriting and why you must use, preserve, and enhance it. Furthermore, you must transmit it to the generations that will follow you.

Growing up in Chicago taught me how to overcome adversity, persevere and succeed. It’s also taught me the meaning of Black Power…how to use it, and more importantly…how to share it.

As I pass my torch to you and our colleagues, I’ll still be by your side since I have no plans to retire soon. Why? Because I’ll never stop doing what sustains me. What is that? Educating and empowering my people.

If you are enjoying The 1960’s Project, please consider making a contribution to the…